Regular readers know that I am a longtime critic of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., in particular his promotion of antivaccine propaganda that contributed to real deaths in a poor nation, his promotion of bizarre conspiracy theories about vaccines and COVID-19, his HIV/AIDS denialism, and, well, just about everything about this overprivileged addled fool. That is, of course, why before the election I characterized RFK Jr. as an “extinction-level threat to federal public health programs and science-based health policy.” Nothing has changed my opinion of him since the election. Indeed, I described Kennedy’s nomination for Secretary of Health and Human Services not long after Donald Trump won the 2024 Presidential election as a “catastrophe for public health and medical research.” And so it has been so far, with President-Elect Donald Trump’s picks for high-ranking federal health positions under his guidance having been a collection of antivaxxers, grifters, and quacks. I mean, seriously: Dave Weldon for CDC Director? He was a hardcore antivaxxer—one of the two or three go-to antivaxxers in Congress for the antivaccine movement—back in the days even before RFK Jr. first inflicted the Simpsonwood conspiracy theory on us. And don’t even get me started on Dr. Mehmet Oz for CMS Administrator, a role in which he would oversee the massive Medicare and Medicaid programs, as well as all programs under the Affordable Care Act. (Come to think of it, maybe “antivaxxers, grifters, and quacks” is too polite a characterization of Trump’s picks thus far.)

Then there’s Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who was recently nominated for NIH Director. Compared to past directors nominated by Presidents of both parties, Bhattacharya is inarguably grossly underqualified, a health economist who, unlike past NIH Directors—seriously, compare him even to the current NIH Director Dr. Monica Bertagnolli—has no record of ever done anything resembling cutting edge biomedical research or run an organization anywhere near as large as the NIH. His sole claim to fame since the pandemic is COVID-19 contrarianism and his attacks on public health as one of the signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration. As you might recall, the GBD was an October 2020 proposal to let the virus rip through the “low risk” younger population, with the futile goal of achieving “natural herd immunity,” with a poorly defined strategy of “focused protection” that would have supposedly kept those most vulnerable to severe disease and death from COVID-19 safe, allowing the presumably young and healthy to die at a much lower rate than the elderly and ill as the virus rampaged through the population. It was a tendentiously libertarian and profoundly social Darwinist approach to “open up the economy” at the expense of disease and death that never would have worked and ultimately did cause enormous damage to public health.

Dr. Jonathan Howard has been doing a bang-up job of calling out certain COVID-19 contrarian physicians who have been of late praising RFK Jr. on their monetized Substacks, to great acclaim from antivaxxers in the comments., all while claiming to be pro-vaccine and blaming provaccine doctors for his ascendency while, risibly, claiming that “sabotaging RFK Jr.’s confirmation will increase vaccine hesitancy.” (Hint: They aren’t, at least not anymore.) Chief among these is, of course, Dr. Vinay Prasad, the UCSF medical oncologist who has made a name for himself by downplaying COVID-19 severity, fear mongering about public health interventions ranging from masking to vaccines (even parroting the antivax message of “do not comply”), and generally weaponizing evidence-based medicine (EBM) against public health science in the name of ideology, even going so far to call for Anthony Fauci and other scientists to be tried and imprisoned (another common antivax refrain). I had thought of piling on a bit more, and this post is (sort of) that, but as I was thinking about what to write today I thought I should zero in on something that Dr. Prasad keeps throwing out there that no other SBM contributor has the experience or background to deconstruct. It’s a small part of the overall promotion of RFK Jr. and his picks from “medical conservatives” like Dr,. Prasad, but it bothers me and, if implemented, would change NIH funding decisions forever—and very likely not in a good way.

Study sections are a waste of time?

I’ve briefly alluded to Dr. Prasad’s idea before, but given Dr. Prasad’s repetition of the idea, more and more I thought I just had to write about it as the issue is, as usual, way more complex than Dr. Prasad portrays it. Is the question of how the NIH doles out research funding to scientists based on their grant applications kind of “niche”? Perhaps, but it’s critically important in a way that even most physicians don’t realize. Prasad began promoting his idea for “reform” of the NIH system for determining who gets research grants on the day after the election, when, among other good things that he thought he saw coming from Trump’s victory, Dr. Prasad wrote on his personal monetized Substack:

The NIH is a failure. It has never tested how to give grant money. We have no idea if the current system is better than modified lottery or other proposal. It has no interest in data transparency, publishing in timely fashion, and reproducibility. The agency also needs a hair cut, and a leader who understands these concerns.

First of all, by any non-ideological measure, the NIH is not a failure. We can argue about whether it’s doing its intended job as well or efficiently as it could, but it’s not a failure. As I put it when I first learned that Dr. Bhattacharya was Trump’s pick for NIH Director, the NIH is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world and arguably the greatest engine of biomedical research ever created. Whatever its flaws—and, as a human-created government institution, it has many—the NIH is about as close to a scientific meritocracy as one can imagine in government (aside, of course, from centers that were created by political meddling, such as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), which studies the sorts of quackery that RFK Jr. likes). No, that is not to say that the NIH can’t be improved, perhaps improved a lot, but NIH-funded research has, directly or indirectly, contributed to innumerable advances in medicine and basic medical science, including the Human Genome Project, gene editing, advances in the understanding and treatment of cancer, HIV/AIDS, and much more. Indeed, the NIH is the envy of most wealthy industrialized nations.

What makes the NIH a “failure,” then? Dr. Prasad doesn’t say other than that in his opinion the NIH has supposedly “never tested how to give grant money.” If you want a better distillation of what I like to call “EBM fundamentalism,” the belief that randomized controlled trials are the only way to test a hypothesis and anything else is useless, I have a hard time thinking of one. It’s the same belief that COVID-19 contrarians have weaponized against public health in general, and vaccines as well, since the pandemic. Indeed, Dr. Prasad himself invoked “RCTs über alles” when he fell for RFK Jr.’s and Aaron Siri’s incredibly misleading longtime antivax trope about vaccines in the CDC schedule not having been all tested against “saline placebo.” What, though, does Dr. Prasad actually mean by a “modified lottery”? I’ve been trying to figure it out; so I did some searches of both his Substack and the group Substack Sensible Medicine for which he’s one of the main bloggers. Unsurprisingly, when Trump announced his nomination for NIH Director, Dr. Prasad thought that Dr. Jay Bhattacharya was a “superb pick” to run the NIH and brought up this chestnut again:

Jay will run randomized trials to figure out which way to give grants is optimal. One study can be the current system vs. a modified lottery, where anyone who passes a basic test of completeness is entered into a lottery. If 5 years later, there is no difference in publications, citations, h indices or any other metric, then it is safe to say study sections are a waste of time.

This has a little more “meat” to the proposal, but only a little. All that Dr. Prasad has has added are three things:

- Grant applications passing a “test of completeness,” whatever this means.

- Adding metrics to examine to determine if there is any difference between the two groups (publications, h-indices, or “any other metric).

- Adding a timeframe.

Readers out there who have had NIH grants or who have ever evaluated NIH grants on a study section will immediately recognize some serious problems here, the first of which is the timeframe. Five years is too brief. It’s often only in the last couple of years of a five year NIH grant—sometimes just the last year!—that the publications start flowing, mainly because the first three or four years are spend doing the background work that leads to the publications. Second, the choice of metrics is rather odd. H-indices have a lot of problems and can be gamed. Finally, just what the heck is a “test of completeness”? The devil, of course, would be in the details. Does “completeness” just mean that the grant application has all the component parts in it? Would there be any criteria, for instance, about what the background, research plan, and other sections of the grant require? What about the usual requirements by the NIH that the grant applicant demonstrate that the research team assembled (co-investigators, consultants, etc.) can actually do the work proposed and that the institutions included in the grant have the actual facilities and expertise to do what is proposed? How would one assess that. It seems to me that one would need something much like a study section.

Also left out of this discussion is the plethora of grant funding mechanisms that the NIH already has. Reading between the lines, what I think that Dr. Prasad seems to be most concerned with is the “gold standard” flagship NIH grant mechanism, the R01. the grant that all biomedical researchers seek. These grants are awarded for five years for as much as hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for a defined research project and are renewable after each cycle, based on progress reports and a new grant application proposing what the PI will do in the next five year cycle. However, the NIH has a number of other grant mechanisms, including the R21 (for early stage research and pilot projects), trainee grants, and small business grants to encourage the translation of discovery into marketable products.

In fairness, though, just because Dr. Prasad has never actually fleshed out this proposal in any serious way (beyond throwing it out there in listicles in two Substack posts) and has never, to my knowledge, actually written a detailed post about the pros an cons of the current study section system for dispensing grant funding versus other systems, “modified lottery” or some of the other mechanisms proposed (e.g., the Howard Hughes Institute method of funding researchers, not projects, and giving them freedom to do whatever they want with the funding they receive), doesn’t mean that there is no merit to the idea. Still, if even Dr. Prasad can’t seem to marshal evidence and arguments for this idea, you might understand why I seem to view it with all the seriousness of his proposal to test the childhood vaccine schedule with “randomized cluster trials,” another proposal that he never fleshed out, despite challenges to do so. So you see why I suspect that the “modified lottery” proposal for NIH funding is as much shitposting something that sounds good to those without category expertise but is ultimately meaningless.

Still, contrary to the whines of someone like Dr. Adam Cifu, we here at SBM do not just “attack.” We analyze and criticize. It turns out that there exist literature and a debate about this idea. Let’s take a look. One thing I immediately noticed, though, is that almost no one is proposing replacing the current system with a “modified lottery,” just experimenting with one. I did find one article proposing replacing the current system not just with a “modified lottery” in which applications are screed for certain criteria but a “pure lottery,” but I doubt that even Dr. Prasad wants to go that far into fantasyland.

Study section vs. modified lottery

Let’s compare the current method of funding grants with the idea of a “modified lottery.” I’ve discussed in extreme detail the current method before, which involves multiple layers of review and evaluation of the grants by committees called study sections, which gather together scientists, physicians, statisticians, and other relevant experts to evaluate grant applications and then come up with a priority score that is the primary metric used to determine which grants receive funding. (As a matter of disclosure, I have served as an ad hoc member on a number of NIH study sections, most recently this September, as well as on the study sections for private foundations.) Generally, with rare exceptions, the NIH funds as many grants as it can using its budgeted funds, starting with applications that garner the lowest priority score—yes, lower is better in NIH scoring!—and working its way up the list of grant applications by priority score until all its funds budgeted for research grants are allocated. It’s a complex system, with multiple layers to screen and evaluate the grant applications submitted, and then to administer the funding and oversee progress reports and applications for renewal (for grant funding mechanisms that allow renewals). It’s also fairly expensive. The FY 2024 budget for the NIH Center for Scientific Review (CSR), which manages all study sections and grant peer review, was $130 million, although this is a pretty small percentage of the overall NIH budget of $47 billion.

I also note that CSR has long been making changes to how the NIH reviews grants, most notably when Dr. Antonio Scarpa (who was the chairman of the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Case Western Reserve University when I was there studying for my PhD) ran CSR. Under his leadership, a number of changes were made to the peer review system, some good, some not-so-good, all of which beyond the scope of this post to discuss. My point is that the NIH has been tweaking and trying to improve its peer review system as long as it has had a peer review system. Just because it hasn’t “tested” a system that Dr. Prasad likes does not mean that it is a “failure.” That’s about as unserious a criticism as I can imagine.

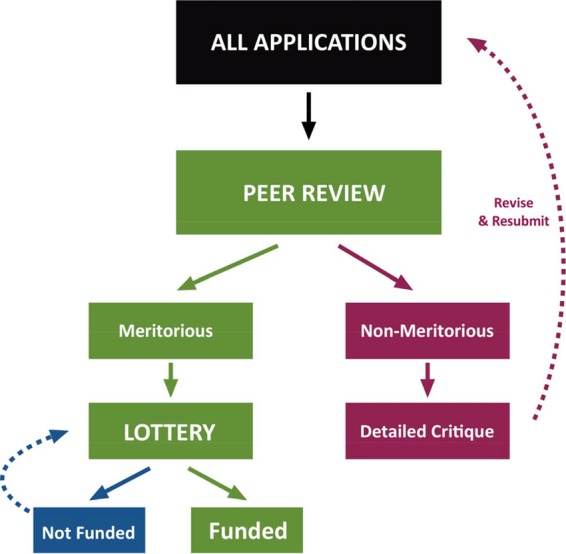

In comparison, a “modified lottery” would introduce some randomness into the process by setting up a system that screens grant applications to pick the ones that meet certain predetermined criteria and then randomly choosing from among those applications the grant applications that would receive NIH funding. For example, in a 2016 editorial advocating a modified lottery, Feric Fang and Arturo Casadevall mapped out such a system thusly:

The idea is that “meritorious” equals anything that achieves a certain priority score, say in the best 20% of scores (or, in NIH lingo, lower than the 20th percentile). I’ll let the authors elaborate:

Given overwhelming evidence that the current process of grant selection is neither fair nor efficient, we instead suggest a two-stage system in which (i) meritorious applications are identified by peer review and (ii) funding decisions are made on the basis of a computer-generated lottery (Fig. 1). The size of the meritorious pool could be adjusted according to the payline. For example, if the payline is 10%, then the size of the meritorious pool might be expected to include the top 20 to 30% of applications identified by peer review. This would eliminate or at least alleviate certain negative aspects of the current system, in particular, bias. Critiques would be issued only for grants that are considered nonmeritorious, eliminating the need for face-to-face study section meetings to argue over rankings, which would bring about immediate cost savings. Remote review would allow more reviewers with relevant expertise to participate in the process, and greater numbers of reviewers would improve precision. Funding would be awarded to as many computer-selected meritorious applications as the research budget allows. Applications that are not chosen would become eligible for the next drawing in 4 months, but individual researchers would be permitted to enter only one application per drawing, which would reduce the need to revise currently meritorious applications that are not funded and free scientists to do more research instead of rewriting grant applications. New investigators could compete in a separate lottery with a higher payline to ensure that a specific portion of funding is dedicated to this group or could be given increased representation in the regular lottery to improve their chances of funding. Although the proposed system could bring some cost savings, we emphasize that the primary advantage of a modified lottery would be to make the system fairer by eliminating sources of bias. The proposed system should improve research workforce diversity, as any female or underrepresented minority applicant who submits a meritorious application will have an equal chance of being awarded funding. There would also be benefits for research institutions. A modified lottery would allow research institutions to make more reliable financial forecasts, since the likelihood of future funding could be estimated from the percentage of their investigators whose applications qualify for the lottery. In the current system, administrators must deal with greater uncertainty, as funding decisions can be highly unpredictable. Furthermore, we note that program officers could still use selective pay mechanisms to fund individuals who consistently make the lottery but fail to receive funding or in the unlikely instance that important fields become underfunded due to the vagaries of luck.

To be honest, maybe it’s just a failure in vision, or maybe I’m just not as brilliant as Dr. Prasad (something that Dr. Prasad, given his massive ego, would certainly agree with), but I fail to see how this system, which seems to be something like what Dr. Prasad proposes, improves on the current system, given that determining which grants are “meritorious” under this system would appear to take nearly almost as much effort and resources as the current study section system. In fact, it could quite conceivably require more work. Why? First, as is noted above, they system could included or require more reviewers, who would have to be paid for their time. However, even leaving that aside, under the current system, during study section it is the grants given the higher priority scores by the three or four assigned primary reviewers that are not discussed because they have no chance of being funded. (This is commonly referred to as an application being “triaged.”) The applicants whose grants are triaged receive the written evaluations of the primary reviewers, but, unlike grants considered to be potentially in the fundable range, there is no discussion or debate. In the cases of better-scoring grants that are discussed, the Scientific Review Officer who organizes and runs the study section meeting will write up a detailed summary of the discussion and add it to the reviews by the study section members assigned primary review.

Of course, I’m not even sure that this is the sort of idea that Dr. Prasad means, because he hasn’t bothered to explain what he means beyond buzzwords, other than referring to a “modified lottery.” Prasad’s idea rather reminds me of the Great Barrington Declaration, in which the proposal is so vague that it is impossible to know what he means in practice, although in fairness even the Great Barrington Declaration, as vague and poorly argued as it was, included more detail in its “natural herd immunity strategy with “focused protection” than Dr. Prasad has about his “modified lottery” idea. One can imagine all sorts of variants of the “modified lottery” system that could be proposed, but one thing is for sure. All of them would still require a peer review system resembling the current study section; that is, unless one goes for a “pure lottery,” which not even Dr. Prasad seems to be proposing.

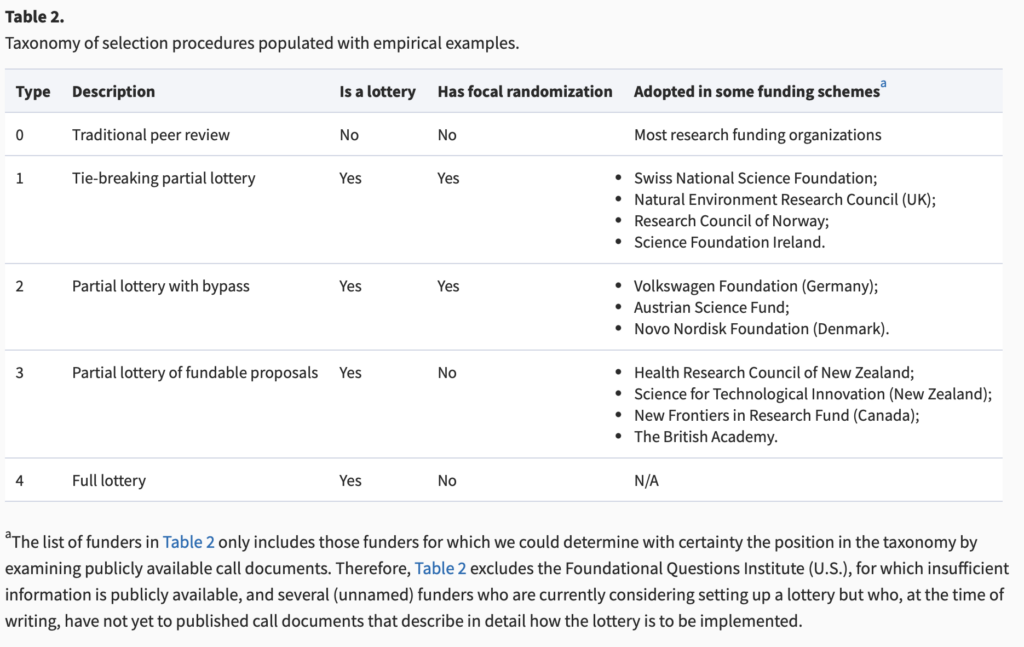

Also, contrary to Dr. Prasad’s have been a number of studies examining whether priority scores for grant applications are predictive of productivity of the PI doing research using the grant funds. Indeed, Feliciani et al recently published a taxonomy of funding mechanisms that involve a lottery, all or in part. Here’s a chart from the review article:

Regarding whatever it is that Dr. Prasad means, I’m quite sure that he doesn’t mean Type 0 or 1 and fairly sure that he doesn’t mean Type 4. What he probably means is Type 2 or 3. Type 3 is a system like the one described in the first article I cited, in which peer review determines which proposals are “meritorious” in the traditional manner, assigning scores to all applications and then choosing a percentage of the best-scored applications based on the anticipated funding line, and then those proposals are funded by lottery. A Type 2 system is a hybrid system in which it is mandated that the funding of proportion of “meritorious” grant applications is determined by peer review, and the rest are placed into a lottery pool. The idea here is to make sure that exceedingly meritorious applications don’t fail to receive funding because of the “bad luck” of a lottery:

Type 2 selection procedures are a different flavor of partial lotteries with focal randomization. While in Type 1 the review panel must come up with a bypass set and may create a lottery pool to resolve ties, in Type 2 the panel must set up a lottery pool.7 The lottery pool typically consists of all eligible proposals deemed to be funding-worthy. Partial lotteries with bypass (Type 2) aim to ensure that excellent proposals are not being missed to bad luck (thanks to the bypass), and also promote a chance for those transformative, innovative or riskier research projects that may be disliked by some reviewers (thanks to the lottery).

Note that Type 2 can be further distinguished by the size of the lottery pool. For example, a funder using a Type 2 procedure may mandate that a number of funding decisions (e.g. 10% of them) is to be determined by lottery (and 90% chosen directly via the bypass): in this case, we can say that the Type 2 lottery is running with a 10% lottery choice rate. A different funder may mandate a 90% lottery choice rate, meaning that 90% of funding awards are chosen from the lottery pool, and only 10% via the bypass. Such lottery choice rates will become important in our simulation experiment and recommendations for funders.

Come to think of it, I don’t think that Dr. Prasad means a Type 2 system. After all, only a fraction (which could range from a small to a large fraction) of “meritorious grants” would be distributed as determined by a lottery.

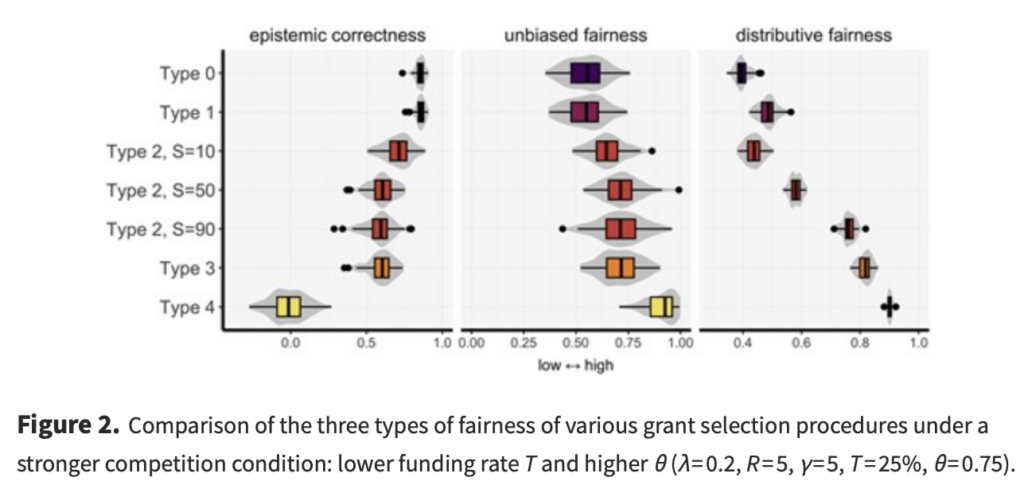

In any event, the authors actually ran simulations of the various methods. You can read the paper in depth if you want, but, to summarize, there was increasing distributive (“funding should be distributed evenly.”) and unbiased fairness (“funding should be distributed without gender, racial, geographic, or other biases.”) as the investigators modeled methods from Type 0 to type 4 that was associated with decreasing epistemological correctness (“funding should go to the ‘best’ proposals”), the effect being less pronounced in terms of epistemological correctness in the high competition condition (low paylines), which, truth be told, has ben the situation with NIH funding since I’ve been faculty. You can get an idea of what I mean from this figure:

As the authors themselves note, this was a modeling study intended to be used to guide research on these methodologies if they are adopted and thus can provide data. Moreover, balancing fairness versus correctness is a policy decision, not strictly a scientific decision. I will also note that under this model a “pure” lottery would produce the worst epistemological correctness with the most fairness, but is that really what we want in an NIH funding mechanism? If the parameters of this model resemble reality, it is impossible to produce a system that is perfectly fair and perfectly able to pick the “best” grant applications, something that anyone who takes some time to think about the issue (unlike Dr. Prasad) is likely to figure out intuitively.

Indeed, one paper frequently cited to argue that the current NIH system poorly predicts which grants will be the most scientifically productive actually rather makes a point that the NIH is actually pretty good at doing just that, just not at differentiating grants that receive the best priority scores. I’ll cite the passage that shows what I mean:

In contrast, a recent analysis of over 130,000 grant applications funded by the NIH between 1980 and 2008 concluded that better percentile scores consistently correlate with greater productivity (Li and Agha, 2015). Although the limitations of using retrospective publication/citation productivity to validate peer review are acknowledged (Lindner et al., 2015; Lauer and Nakamura, 2015), this large study has been interpreted as vindicating grant peer review (Mervis, 2015; Williams, 2015). However, the relevance of those findings for the current situation is questionable since the analysis included many funded grants with poor percentile scores (>40th percentile) that would not be considered competitive today. Moreover, this study did not examine the important question of whether percentile scores can accurately stratify meritorious applications to identify those most likely to be productive.

We therefore performed a re-analysis of the same dataset to specifically address this question. Our analysis focused on subset of grants in the earlier study (Li and Agha, 2015) that were awarded a percentile score of 20 or better: this subset contained 102,740 grants. This percentile range is most relevant because NIH paylines (that is, the lowest percentile score that is funded) seldom exceed the 20th percentile and have hovered around the 10th percentile for some institutes in recent years.

It is true that the study found that there was little or no difference between grant applications in the best-scored 20% of all applications in terms of the chosen outcome metrics of publications (e.g., publications). In other words, it found that, contrary to what is implied by Dr. Prasad that the NIH study section system is a “failure,” in actuality study sections are quite effective in identifying the most scientifically meritorious applications out of the whole pool of applications. They just can’t stratify the really good applications that garner the best scores finely enough to predict which of them will be most productive; in other words, they’re a (somewhat) blunt tool. Indeed, scientists (including myself) have been saying this sort of thing before, mainly that when paylines are only around the 10th percentile (or, as they have been frequently over the last 20 years, even lower), it becomes a crapshoot—a lottery, if you will—which really excellent grant applications will be funded, and certain really great grant applications will fail to be funded—and not because they aren’t great grant applications that deserve to be funded. After all, what objective criteria are there to distinguish between a grant with a priority score at the 7th percentile versus one at the 8th percentile. Yet, funding decisions need to be made because there is only a finite pool of money, and therefore a cutoff needs to be decided. Indeed, I have frequently said that the solution to this problem, which contributes to NIH study sections being conservative and tending to fund “safer science” is to provide more funding, so that the paylines rise, not necessarily to radically alter the study section system.

Still, even though it’s Dr. Prasad making the proposal, a modified lottery is not necessarily inherently a bad idea, given that it’s far more likely that the Trump administration will cut, rather than increase, the NIH budget, the best case scenario likely being that the NIH sees no significant increase in funding adjusted for inflation during the next four years. The problem, of course, is that it’s hard to figure out just what the heck Dr. Prasad is actually proposing. As far as I can tell based on his advocating that the grants to be distributed by lottery, he seems to be proposing a system more like the Type 4 system in the taxonomy above than a Type 3 system. Remember, the Type 3 system involves the grant pool being winnowed down to the small percentage of grants deemed “meritorious,” perhaps two to three times the number of grants as can be funded, and then that pool being used to pick the winners randomly by lottery. It would involve a lot more than just a “basic test for completeness” to accomplish that.

Then there’s the issue of how one might do a “randomized trial” of the current system versus the system that Dr. Prasad proposes that includes a modified lottery? Does he even have any idea of how difficult such a trial would be to design and carry out? Just think about it a minute. You’d have to set up another parallel system for evaluating grants, and then find a way to randomly assign new grant applications to one or the other. You can bet that a lot of the more prominent and longer-funded NIH grant recipients would do their damnedest to game the system to get their grants assigned to the old system, and you can also bet that the ones who are assigned the new system and fail to win funding will use every last step of the NIH appeal process that the can come up with, not unconvincingly arguing that they were unfairly treated because they weren’t treated like everyone else. Again, just like his risibly bad proposal for a “cluster RCT” of childhood vaccination schedules based on states or counties, Dr. Prasad’s proposal for a randomized trial of the old study section system with his idea (if he can flesh it out) of a “modified lottery reveals just out out of touch with reality he’s become in his ivory tower at UCSF, protected from any hint of critical thinking from the audience that has captured him.

I will conclude this section by reiterating that including some sort of modified lottery in the grant approval process is not an entirely crazy idea. Researchers (myself included) have long complained that, once you get a priority score that’s in the 10th percentile or below, it’s impossible reliably differentiate between them in terms of which applications are more scientifically meritorious. It’s not entirely unreasonable to score the grants, pick the best 20-30% for a lottery, and then decide which ones receive funding based on a lottery or a combination involving picking “the best of the best” in the pool and then using a lottery to choose among the “rest of the best.” Again, though, that does not appear to be what Dr. Prasad is proposing. Truth be told, I don’t think that even Dr. Prasad knows what he’s proposing. He just knows that he really detested the NIH leadership during the pandemic, particularly Anthony Fauci and Frances Collins, and that, just because he didn’t like how the NIH performed during the pandemic (even though the NIH was not responsible for public health interventions or approving vaccines), he concludes that the NIH “has failed” in everything else that it does, particularly peer review of grant applications by its study sections. In this, he has allowed his personal bias added to his EBM fundamentalism, all coupled with his love of shitposting, to lead him to make a profoundly unserious proposal. I like to think that Dr,. Prasad knows better but also knows that his audience does not know better, but I’m starting to wonder if he is genuinely ignorant about how NIH grants are allocated and doesn’t care to educate himself.

Same as it ever was. But why?

An axe to grind?

One wonders why Dr. Prasad would keep repeating this proposal, even though he sure appears unable to say exactly what he means by it. I must confess that I have an idea. To me, it definitely seems that Dr. Prasad has an axe to grind about the NIH based on his having trained there, having done his hematology/oncology fellowship at the National Cancer Institute. Two years ago, when Dr. Prasad was promoted to full professor, he wrote:

Professors should have time to think, but this has been devalued. In a soft money world, I often feel like a Mary Kay salesperson—holding a job with no guaranteed income—where you are perennially hunting for open shifts or grants or teaching slots to fund yourself. I have been deeply fortunate to be grant-funded by an incredibly ambitious and visionary philanthropic organization: Arnold Ventures. At the same time, I have repeatedly seen the limitations of the NIH. That is why I agree with Adam Cifu that with each 5 years after being an associate professor, 10% of your time should be bought out by the university.

This is, of course, a not-uncommon complaint about the current model for biomedical research in academia, although the problem of one’s entire salary only being partially funded by one’s university, with the researcher expected to fund the rest through grants, is primarily an issue for research faculty. The salaries of clinical faculty are usually funded through a combination of university funding plus reimbursements for clinical services rendered to patients, either through an individual “you eat what you kill” model or through a more “socialist” model in which clinical faculty are paid salaries from the pooled clinical income of their departments, with some clinicians who bring in a lot more revenue than their expenses subsidizing the salaries of others—usually those doing a significant amount of research or who are in low-reimbursement specialties (like breast surgery)—who don’t manage to cover their expenses with clinical income. My understanding is that Dr. Prasad is just. 0.2 FTE, meaning that he is only 20% clinical, with 80% being research and everything else; so I get it. Also, tenure means something different to clinical faculty; generally, it only guarantees the university part of their salaries. Unfortunately, most clinical faculty derive most of their salaries from clinical income, which is why I frequently say that, to us, tenure is much less of a big deal, other than the prestige that comes with it.

If he ever were to lose his research funding, Dr. Prasad would likely have to join the many MDs who devote more than 50% of their time to research who ultimately find themselves shifting their activities to more and more clinical work because it’s become more and more difficult to obtain grant funding to cover the academic/research part of their salaries. One also notes that, never having received NIH funding (more on this below), Dr. Prasad seems to have found as an alternative to the NIH an ideologically aligned sugardaddy in Arnold Ventures, a private investment fund created by ex-Enron hedge fund billionaire John Arnold, for projects that help hospitals reduce costs, usually by cutting “unnecessary” or “low-value” care, which aligns pretty well with Dr. Prasad’s opposition to public health interventions. To be fair, though I must point out that, on the other hand, Arnold Ventures has supported Ben Goldacre and that “Second Amendment” activists really hate Arnold Ventures because it also funds research into causes of and solutions to the problem of gun violence; so maybe it’s not all bad. It isn’t the NIH, however, and Arnold Ventures has also supported food crank Gary Taubes, who claims that saturated fat does not contribute to obesity. Back in the day, we wrote a number of articles about Taubes’ claims about sugar and his claim that it isn’t “calories in/calories out” that determines obesity but what you eat, regardless of calories.

In any event, Dr. Prasad continued:

During residency I expected to love cardiology, but it never clicked. Instead, H.G. Munshi, Shuo Ma, and others showed me how fascinating hematology and oncology could be. I went to the NIH with the vague idea that one could combine interest in oncology, EBM and regulatory science, and briefly contemplated working at FDA. But I quickly learned our current Oncology FDA was less committed to EBM than it was to helping for-profit companies bring products to market. Tito Fojo, Susan Bates, Barry Kramer, Sanjeev Bala, Sham Mailankody and many others at NIH influenced my thinking. My virtual mentors grew to the hundreds, as I poured through old issues of JCO, NEJM, JAMA and many others. They included Korn, Freidlin, Tannock, Sargent, Moertel, and countless others. I loved my time at NIH and was very productive there; Cifu and I finished our Reversal book in my final year.

To be brutally honest, I’ve long suspected that one reason why Dr. Prasad is so hostile to the current system of determining which grant applications receive NIH funding comes from his never having received NIH funding as a PI. I went to NIH RePorter, the NIH’s searchable database for all of its funding, where you can look up any grant funded since 1985. A search for “Vinay Prasad” under principal investigator pulled up four active grants, three to Dr. Vinayaka Prasad, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for HIV/AIDS research, the other to the World Health Organization for tobacco regulation research. Expanding the search to all fiscal years in the database brought up lots of grants by Dr. Vinayaka Prasad for HIV/AIDS research at Albert Einstein going back to 1991. Bottom line: It looks as though, unlike myself, Dr. Prasad has never been the PI on an NIH grant. Granted, I haven’t been PI on an NIH grant since 2011; so I understand the frustration.

The difference between Dr. Prasad and me is that I view my inability to be funded by the NIH since 2010 (except as co-investigator on other projects) more as my failure, not a manifestation of the NIH being “broken.” Basically, I was “good enough” scientifically when NIH paylines were a little more generous (as they were in 2005), but no longer “good enough” after they fell to their current low levels. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve discussed problems with NIH funding mechanisms before, mainly its conservatism in terms of funding “safer” science, but that conservatism tends to be a product of low funding. When you can only fund, say, 8% of grant applications that come through, taking a risk becomes more difficult, as I discussed above and here. That I was a casualty of that lower funding is painful, but I nonetheless take the more realistic view that what was once “good enough” no longer is and then try to move on. In contrast, Dr. Prasad blames the system 100% and doesn’t even accept that at least part of the reason why he hasn’t been funded by the NIH is himself.

As I alluded to earlier in this post, when in the course of discussing and deconstructing and refuting a proposal being promoted by an influencer like Dr. Prasad better than the influencer himself can defend (or even describe it), that’s often an indication that the influencer making the proposal is profoundly unserious about it. I believe that’s the case here with Dr. Prasad, just as it was when he said that he thought that RFK Jr. had some good ideas, specifically his opposition to the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine and his agreeing with RFK Jr.’s highly deceptive claim and longtime antivax trope implying that the childhood vaccine schedule is not safe because it hasn’t been “adequately tested” against saline placebo, complete with repeated calls for an unethical, impractical, and unfeasible “cluster RCT” of childhood vaccine schedules. Both are claims that betray a lack of knowledge and—dare I say?—seriousness about scientific and policy issues involved.

If that isn’t enough, then consider this. Dr. Prasad and his fellow RFK Jr. sycophants, toadies, and lackeys complain that there is bias in NIH funding. For example, Dr. Prasad decries what he perceives to be the “wokeness” of the NIH in the form of funded studies looking at strategies to provide access to cancer screening tests to homeless people. All that goes along with his rants about “woke” agendas in medical schools. No wonder Dr. Prasad seems utterly unconcerned about proposals being openly proposed by Dr. Bhattacharya that would withhold research grants from schools that Donald Trump and his allies consider too “woke”:

Trump’s nominee to head the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, a physician and economist at Stanford, reportedly wants to target so called “cancel culture” at a number of top progressive universities, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Those with knowledge of Bhattacharya’s thinking told the newspaper that he’s considering linking the doling out of billions in federal research grants to a measure of “academic freedom” on campuses and punishing those that apparently don’t adequately embrace perspectives championed by conservatives.

Bhattacharya wants to take on what he views as academic conformity in science, which pushed him aside over his criticism of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including his opposition to school closures and mask mandates to stop the spread of the virus. He suggested in a Wall Street Journal op ed in 2020 that only up to 40,000 Americans would be killed by the pandemic. More than 1.2 million people died.

Seriously, it’s Lysenko all over again, and these sorts of proposals for ideological tests of purity are a dagger aimed at the heart of biomedical research and utter anathema to the scientific culture at the NIH—to scientific culture in general. Indeed, the only people who have made such proposals before have tended to be ideologically biased legislators (e.g., Sen. Tom Harkin, who. foisted the NCCIH on the NIH, or Rep. Darrell Issa, who tried to torpedo a study of HIV/AIDS because he didn’t like the methodology). That’s yet another reason that NIH study sections are far from a waste of time. They do distinguish scientifically meritorious proposals from those that are lacking; they just aren’t a fine enough measure to reliably distinguish between excellent proposals. That’s why we should continue to study strategies to improve how study sections operate, in order to increase their scientific rigor and decrease any bias, and I’m not against adding the element of a lottery to choosing among proposals that are highly meritorious whose success and output the current system doesn’t predict accurately. However, if some of the anti-“cancel culture” proposals of Dr. Bhattacharya are implemented, such that a schools’ politics matter as much or more than the quality of its research proposals, any improvements or “reforms” made to the NIH peer review system would end up being akin to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic after it hits the iceberg of Trumpian political correctness as interpreted by RFK Jr. and Dr. Bhattacharya. Dr. Prasad is unconcerned about that because it’s a form of political correctness that he likes. Most likely, he views it as vindication and just revenge upon his harshest critics.

“Profoundly unserious” doesn’t even begin to describe that, nor does it describe Dr. Prasad’s lack of description of just how one would do a “randomized trial” of the two evaluation systems. Seriously, does Dr. Prasad even think about what he’s proposing? It sure doesn’t look as though he does, but, then, thought is unnecessary, at least scientifically-based thought. He’s not making these proposals for an audience of scientists. He’s making them for an audience of ideologues who don’t know how vaccine schedules are constructed or how the NIH works.